Dive Deeper Into the Rich History of Elgar's Enigma

In England, Variation 9, “Nimrod” has become a kind of musical shorthand for Englishness itself. This solemn, stately music has also made its way into popular culture through film scores: Australian composer Rob Dougan’s 1995 hit, “Clubbed to Death,” which is grounded in the harmony of Elgar’s original theme and also references the melody, became part of the soundtrack for the blockbuster 1999 film The Matrix; Hans Zimmer also used it in the score to the 2017 WWII film Dunkirk. In 2012, “Nimrod” was performed at the London Olympics opening ceremony. It is also played every year in Britain on Remembrance Sunday.

Much has been written about the Variations, including lengthy discussions of their actual title. Elgar called them simply Variations for Orchestra on an Original Theme. The word “enigma” was added by Elgar’s publisher August Jaeger above the original theme in the manuscript, suggesting “Enigma” was the name of the theme itself, rather than the title of the whole work. Furthermore, the title page reads, “Variations for Orchestra composed by Edward Elgar Op. 36.” This was later changed to “Variations on an Original Theme for Orchestra, Op. 36.” Elgar himself never referred to Op. 36 as the “Enigma Variations” in his conversations and correspondence, although he did not object to the nickname appearing in the published score.

How “Enigma” was born

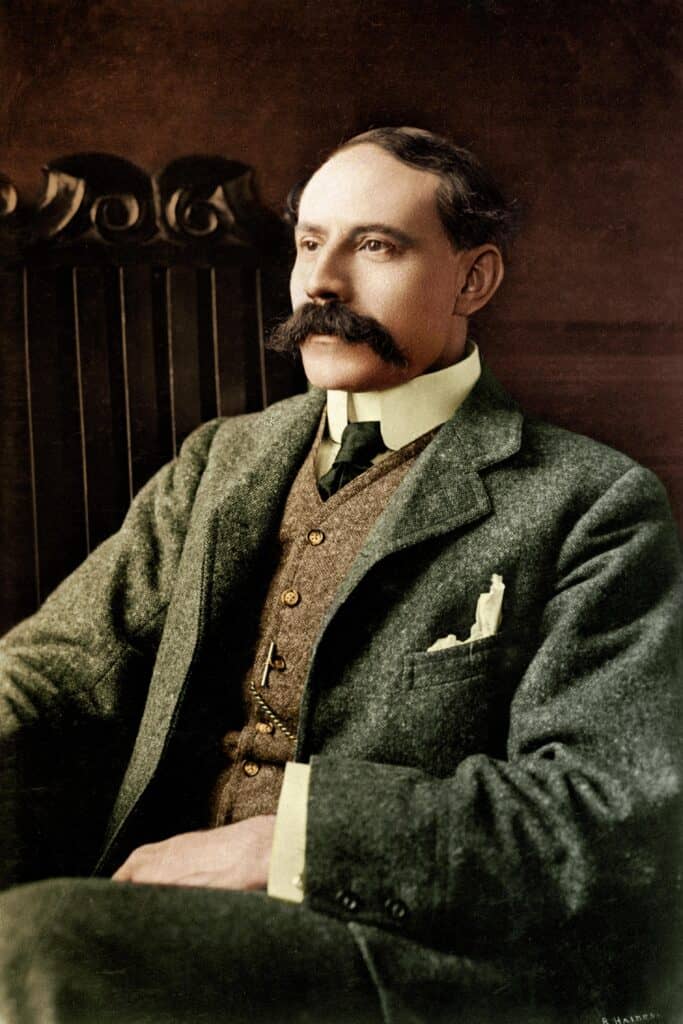

One chilly October night in 1898, Elgar came home after a long day of teaching violin lessons. To unwind, he sat down at his piano and began improvising. Elgar recalled, “Suddenly my wife interrupted by saying, ‘Edward, that’s a good tune.’ I awoke from the dream, ‘Eh! Tune, what tune?’ and she said, ‘Play it again, I like that tune.’ As he repeated it, he began to vary it, asking her, “Whom does that remind you of?” and thus the musical portraits of the “friends pictured within” were born.

There are two enigmas in the Variations: the melody that begins the piece; and another, which according to Elgar, is silent but

present throughout. In Elgar’s original program notes for the June 1899 premiere, he wrote, “The enigma I will not explain –

its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the apparent connection between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’ but is not played.” Because Elgar never revealed the identity of the enigma, speculation about it abounded, both during Elgar’s lifetime and perhaps even more so after his death in 1934. Over the years “Rule Britannia,” “God Save the King,” “Auld Lang Syne” and the hymn “Ein feste Burg” (A Mighty Fortress Is Our God) have all been suggested as possible candidates.

Some scholars suggest, in keeping with Elgar’s comment regarding the “silent” enigma, that the second enigma is not a piece of music at all but an abstract concept, such as friendship or love. 12 years ago, two musicologists published an article, “Solving Elgar’s Enigma,” which postulates the intriguing theory that the silent enigma is pi (π), the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter.*

With the success of the Variations, English music itself, which had languished in relative obscurity since the death of Henry Purcell some 300 years earlier, received a much-needed boost. Op. 36 immediately delighted audiences with its thirteen portraits of Elgar’s friends and family, and his own self-portrait finale. His love of puzzles notwithstanding, Elgar intended this loving tribute to be appreciated as pure music; he insisted one need not know the enigma’s solution to enjoy listening to it. Elgar wrote, “There is nothing to be gained in an artistic or musical sense by solving the enigma of any of the personalities; the listener should hear the music as music, and not trouble himself with any intricacies of ‘programme.’ To me, the various personalities have been a source of inspiration, their idealisations a pleasure – and one that is intensified as the years go by.

According to Elgar, the audible enigma (Original Theme) represents the composer himself; he felt it embodied the loneliness of the creative artist. In a letter to Jaeger, Elgar wrote, “I have sketched a set of Variations (orkestra) on an original theme: the Variations have amused me because I’ve labeled ’em with the nicknames of my particular friends – you are Nimrod. That is to say I’ve written the variations each one to represent the mood of the ‘party’ – I’ve liked to imagine the ‘party’ writing the var: him (or her) self and have written what I think they wd. have written – if they were asses enough to compose – it’s a quaint idee & the result is amusing to those behind the scenes & won’t affect the hearer who ‘nose nuffin.’ What think you?”

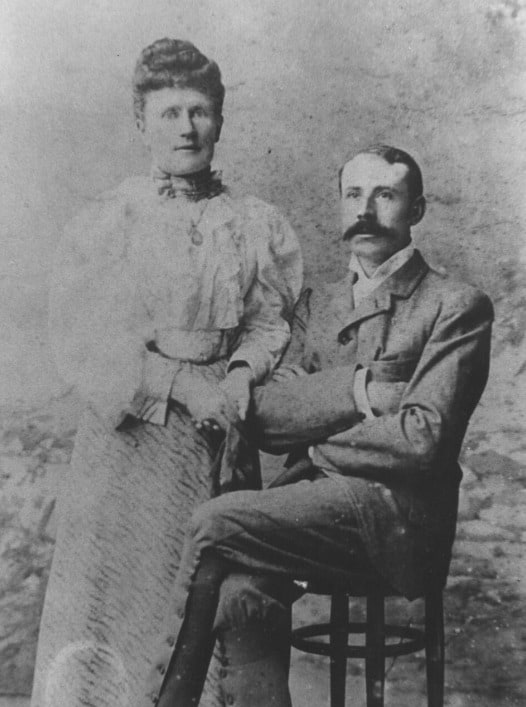

The people Elgar pictured are close friends and family; there are no famous musicians or influential aristocrats. Elgar himself was a man of humble birth, who felt a life-long alienation from the English upper classes; his marriage to his wife Alice was regarded (on her side of the family, at least) as a case of “marrying up.” Whatever Alice’s family thought of Elgar, she knew that Elgar did not marry her to gain status or position, but out of love and devotion.

The “Friends Pictured Within:”

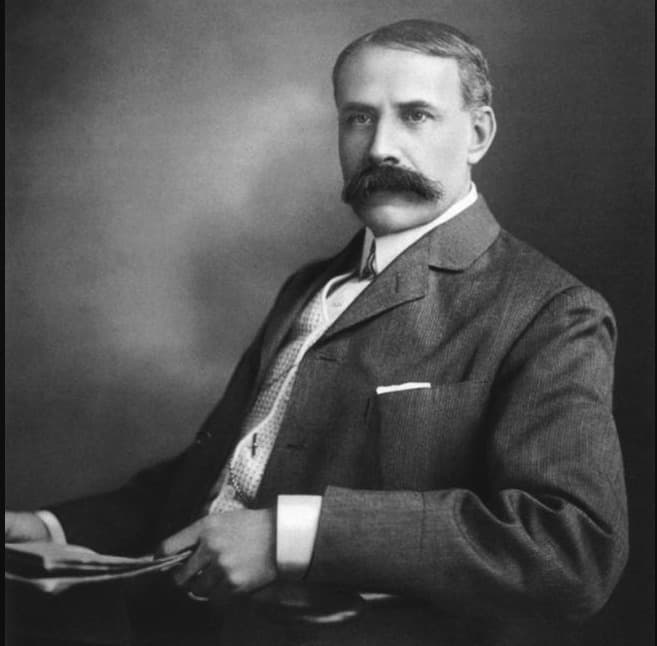

1. C.A.E. Caroline Alice Elgar (1848-1920)

Elgar’s wife. Known as Alice, she was the daughter of a retired major-general who served in India. She was a woman of many interests, including geography (she herself was born in India), natural history, and literature. She published a novel and a fair amount of poetry, some of which Elgar set to music. In her late 30s, Alice began studying piano accompaniment with Elgar, and after her mother died in 1887, they fell in love. Her family were scandalized at the idea of her marrying Elgar, who was poor, Catholic, and whose father was “in trade.” Alice, however, was undeterred. She believed in Elgar, loved him, and throughout the 31 years of their marriage she was Elgar’s most consistent and faithful supporter. According to Elgar, her life “… was a romantic and delicate inspiration.” The music of her variation suggests this; it begins as a gentle, refined reworking of the opening Enigma theme, (Elgar said it was “really a prolongation of the [Enigma] theme”), transforms into a passionate exclamation of emotion, and ends serenely

2. H.D.S-P. Hew David Steuart-Powell (1851- 1924)

An amateur pianist who often played piano trios with Elgar and Basil Nevinson. His typical piano warm-ups, which favored diatonic scales, are satirized in a way Elgar described as “chromatic beyond H. D. S.-P.’s liking.” The strings and winds are agitated throughout this brief, breathy variation.

3. R.B.T. Richard Baxter Townshend (1846-1923)

A well- traveled and rather eccentric scholar/author. His youthful adventures included cattle ranching in Texas and prospecting for gold in Colorado; his American experiences gave him an interest in and sympathy for the plight of the American Indian. Townshend later taught Classics at Bath College and was also a gifted mimic and amateur actor. His theatrical caricature of an old man amused Elgar, who described ‘the low voice flying off occasionally into ‘soprano’ timbre.’ It is this caricature (rather than an actual portrayal of Townshend himself) that is the subject of the variation, which, correspondingly, features high and low extremes of pitch and timbre.

4. W.M.B. William Meath Baker (1858-1935)

The squire of Hasfield Court, and an avid Alpine climber. The Elgars enjoyed his hospitality on several occasions, where they witnessed his habit of barking commands to his guests and slamming doors upon exiting rooms. Elgar highlighted Baker’s tempestuous behavior in this shortest of the variations (just 32 measures)

5. R.P.A. Richard Penrose Arnold (1855-1908),

Third son of poet Matthew Arnold. He was a pianist whose self taught style of playing, according to Elgar, seemed to be “evading difficulties but suggesting in a mysterious way the real feeling. His serious conversation was continually broken up by whimsical and witty remarks.” The pensive minor-mode quality of the opening suggests a dreamy, sensitive personality, and the contrasting section for winds in major evokes the “whimsical and witty remarks.”

6. Ysobel Isabel Fitton (1868-1936)

A talented amateur musician who played piano and violin. Elgar started her on viola lessons as well, but she ceased working with him,

saying, “No, dear Edward, I value our friendship much too much!” Her variation is modeled after a viola exercise Elgar designed for her to practice crossing strings, something she apparently had difficulty mastering, and it features a short passage for solo viola. Elgar described her variation as “pensive, [but] for a moment, romantic.”

7. Troyte Arthur Troyte Griffith (1864-1942)

An artist, architect, and not-overly-talented piano student of Elgar’s, who said that he tried “… to make something like order out of the chaos,” but that “…the final despairing ‘slam’ records that the effort proved to be in vain.” Some Elgar scholars describe this variation as a musical depiction of a walk Elgar and Troyte took in the Malvern Hills, in which they were surprised by a thunderstorm. The booming of the timpani at the opening corresponds to thunder, and the energetic music can be interpreted to suggest a violent cloudburst.

8. W.N. Winifred Norbury (1861-1938)

Co-secretary of the Worcestershire Philharmonic Society. She also, with Lady Mary Lygon, another possible “friend pictured within,” co-directed the Madresfield Musical Society. (In his sketches for this variation, Elgar wrote the note “secys,” which suggests the intent to honor Norbury and Monica Hyde, the secretaries of the Worcestershire Philharmonic Society.) Elgar said this variation is actually a portrait of “Sherridge,” Norbury’s beautiful house, the scene of numerous musical gatherings. The bubbling winds capture her ready laugh.

9. Nimrod August Johannes Jaeger (1860-1909)

A good friend and one of Elgar’s publishers at Novello (Nimrod is the biblical “mighty hunter,” a pun on “Jaeger,” the German word for “hunter.”) Jaeger was not only Elgar’s publisher, but also his champion, and he made useful and important constructive criticisms of Elgar’s music, like in particular, expanding and lengthening the finale of the Enigma Variations, which Elgar greatly appreciated.

When Elgar and Alice visited Jaeger on Jan. 12, 1899, Elgar told Jaeger of his failed attempts to interest Novello in the Variations, and that he was going to give up composing and go back to teaching music. Jaeger, disturbed by this news, took it upon himself to ensure Elgar’s Variations would receive the attention they deserved. Within a day or two of Elgar’s visit, Jaeger went to composer Sir Hubert Parry (best known for the church anthem “Jerusalem”), and described Elgar’s plight. Parry took Jaeger to the home of Hans Richter, who was then conductor of the Birmingham Festival and his own series of London concerts. Richter was in Vienna, but Parry and Jaeger contacted his London agent, who promised to send the manuscript of Elgar’s Variations on to Richter with a positive recommendation. (Richter was impressed and interested in the Variations, and his endorsement led to their dissemination in Europe.)

Elgar described Jaeger’s variation as an evocation of a conversation between the two men about Beethoven’s difficulties with his deafness. Jaeger’s mention of Beethoven was meant to encourage Elgar, who was at the time despondent over his own struggles to gain recognition. Elgar wrote, “it will be noticed that the opening bars are made to suggest the slow movement of [Beethoven’s] Eighth Sonata (‘Pathétique’).”

10. Dorabella Dora Penny (1874-1964)

Nicknamed “Dorabella” by Elgar, after a character in Mozart’s opera, Così fan tutte. She met the Elgars in 1895 and Alice soon hired her as an archivist of Elgar’s papers. She is described as having “youthful charm,” epitomized by her spontaneous improvised dances to Elgar’s music (she also accompanied Elgar on bicycle rides around the countryside). She often sat at the piano turning pages for Elgar during performances. In 1937, three years after Elgar’s death, she wrote Edward Elgar: memories of a variation, which is a loving but not particularly accurate memoir. Her variation features a gentle stutter in the woodwinds, which mimics Penny’s actual minor speech defect; this was Elgar’s affectionate attempt to both tease and characterize her musically.

11. G.R.S. George Robertson Sinclair (1863-1917)

Organist of Hereford Cathedral. He is the only professional musician (other than Elgar himself) associated with the Variations; soon after he came to Hereford Cathedral, in 1897, he commissioned the Elgar’s Te Deum and Benedictus. Elgar appreciated Sinclair’s musical abilities, but the variation named for Sinclair is actually a portrayal of his bulldog, Dan. We hear Dan tearing about with typical canine energy, fetching and retrieving sticks from the Wye River, and tumbling down the riverbank. Elgar made a habit of noting ideas, which he called “the moods of Dan,” in Sinclair’s visitor’s book. Some of these musical jottings were used in Elgar’s other works, including The Dream of Gerontius.

12. B.G.N. Basil Nevinson

An amateur cellist who played with Elgar and Steuart-Powell. He was a barrister by profession, although he did not practice law. Elgar described him as ‘a serious and devoted friend … whose scientific and artistic attainments, and the whole-hearted way they were put at the disposal of his friends, particularly endeared him to the writer.” Nevinson’s playing may have inspired Elgar to write his Cello Concerto. This variation, not surprisingly, begins with a solo cello melody, and the cello section is featured throughout. This variation is musically more similar to the Enigma theme than the other variations.

13. ***

There has been more discussion about this variation than any other, because it does not definitively identify anyone, and also bears the title “Romanza.” The possible candidates for this variation are women, which leads to speculation of a romantic nature similar to that surrounding the identity of Beethoven’s Immortal Beloved.

Elgar himself claimed Lady Mary Lygon (1869-1927) was the inspiration for this variation, but if so, why hide her identity? Elgar also claimed Lygon traveled to Australia at the time Elgar composed the variation (in fact, she was still in England), and to bolster the nautical association, he quotes from Mendelssohn’s Calm Seas and Prosperous Voyage.

Elgar’s former fiancée Helen Jessie Weaver is another possibility. Elgar had known her from childhood; by some accounts, she broke his heart when she emigrated to New Zealand. The passion he felt for her has been interpreted by some scholars as being evident in the mood of the Romanza.

14. E.D.U. Elgar.

“Edoo” was Alice’s pet name for her husband, a variation of the French “Edouard.” His variation quotes from hers and from Jaeger’s, the two people who consistently believed in and supported him throughout his life. “Written at a time when friends were dubious and generally discouraging as to the composer’s musical future,” said Elgar, “this variation is merely intended to show what E.D.U. intended to do. References are made to two great influences upon the life of the composer: C.A.E. and Nimrod. The whole work is summed up in the triumphant broad presentation of the theme in the major.”

Elgar’s English colleagues immediately appreciated what the Enigma Variations represented, both to British people and to audiences throughout Europe. Sir (Charles) Hubert Parry, an English composer best known for the choral anthem “Jerusalem,” recorded in his diary his pleasure at hearing that “[conductor Hans] Richter is going to preside over their presentation to the Viennese. It will wake them up and no mistake.” Richard Strauss announced, “Here for the first time is an English composer who has something to say.” Elgar’s mother Ann also understood the significance of her son’s success. In a letter to Elgar’s wife Alice, Ann wrote, “I feel that he is some great historic person – I cannot claim a little bit of him now he belongs to the big world.”

If you want to learn more about possible solutions to Elgar’s enigma, check out composer Barnaby Martin’s YouTube channel Listening In, particularly The Mystery Behind Elgar’s Enigma

© Elizabeth Schwartz