Dvořák 8

190 S. Cascade Ave

Colorado Springs,

CO

80903

United States

+ Google Map

Program

Ives Three Places in New England

Schumann Concert Piece for Four Horns and Orchestra

Dvořák Symphony No. 8

About The Performance

This exciting and varied evening offers up the American master Charles Ives’ sonic ode, followed by Robert Schumann’s marvelously scored showpiece for four french horns. We conclude with Antonin Dvořák’s Symphony No. 8, resplendent in folk melodies and pastoral scenes reminiscent of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony.

Join us for Colorado Springs Philharmonic Pre-Concert talks. Go behind the curtain and inside the score with these 30-minute pre-concert conversations featuring conductors and guest artists giving their take on the program. Talks begin one hour before performance time.

Read More

Three Places in New England

CHARLES IVES (1874 –1954)

Composer: born October 20, 1874, Danbury, CT; died May 19. 1954, New York City

Work composed: 1903-11, rev. 1929, 1933-5

World premiere: Nicolas Slonimsky led the American Committee of the International Society for Contemporary Music on February 16, 1930, in New York

Instrumentation: 3 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 3 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, gong, snare drum, harp, piano, celeste, and strings

Charles Ives’ inimitable style, which combines bursts of vivid colors and rhythms with gentler passages, layered with fragments of recognizable tunes but rarely a conventional melody, shocked friends and colleagues. One day in 1912, Ives played “Boston Common” and “Putnam’s Camp” for Max Smith, music critic for the New York Press. When Ives finished, Smith exclaimed, “These were awful! How can you like horrible sounds like that?” Conductor Nicolas Slonimsky, however, appreciated Ives’ unique approach. In his autobiography Perfect Pitch, Slonimsky described his first reaction to Three Places: “As I looked over the score, I experienced a strange but unmistakable feeling that I was looking at a work of genius.”

In a uniquely American manner, the music of Three Places in New England emerged from Ives’ stream-of consciousness impressions of three specific places. Ives’ musical vocabulary includes seemingly unrelated components: quotes from church hymns and marching band music, impenetrably dense bunches of notes known as tone clusters, and the aural confusion produced by familiar melodies played simultaneously in discordant keys.

For Ives, this collage approach to composition best reflected his musical experiences of the world. “The ‘Saint-Gaudens’ in Boston Common (Col. Shaw and his Colored Regiment)” includes fragments of three familiar songs of Ives’ day: Stephen Foster’s “Old Black Joe,” and the Civil War songs “Marching Through Georgia,” and “The Battle Cry of Freedom.” Ives also wrote a poem to accompany his musical commemoration of sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ memorial to Civil War Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th, the first all-Black Union regiment, whose story was dramatized in the 1989 film Glory.

Saint-Gaudens’ massive bronze bas-relief stands at the top of Boston Common, facing the Massachusetts State House. “Near Redding Center, Conn., is a small park preserved as a Revolutionary Memorial; for here General Israel Putnam’s soldiers had their winter quarters in 1778-1779,” Ives wrote by way of introduction to “Putnam’s Camp, Redding, CT.” Ives goes on to describe an imaginary 4th of July celebration at the historic campground, as seen and heard through the eyes and ears of a young boy.

Children’s laughter, hot summer sun, and scattered picnickers give way to a acophonous “Battle of the Bands:” two marching bands play different marches simultaneously. “In this music, inspired by a poem by Robert Underwood Johnson, I captured a memory of a Sunday morning walk that Mrs. Ives and I took the summer we were married [1908], in the meadows along the [Housatonic] river, and heard the distant singing from the church,” wrote Ives. “The mist had not entirely left the river bed, and the colors, the running water, the banks and the elm trees are something that one would always remember.” The Housatonic murmurs throughout the music, mingling with quotes from several well-known hymns. Ives’ music captures the Housatonic’s quiet eddies and deceptively still surface, with occasional sparkling iridescences glinting between the river’s shaded banks.

Concert Piece in F for 4 Horns

and Orchestra, Op. 86

ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810 – 1856)

Composer: born June 8, 1810, Zwickau; died Endenich, nr Bonn, July 29, 1856

Work composed: 1849

World premiere: Julius Rietz led the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra on February 25, 1850, in Leipzig, with the orchestra’s horn section as featured soloists

Instrumentation: 4 solo horns, piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings

Any horn player will tell you their instrument is one of the most difficult to get a decent sound out of, and many non-hornists agree. As challenging as it is to play a modern horn well, it was infinitely harder for hornists from previous centuries. Before 1818, horns had no valves, and could only play a limited number of notes; pitch changes were made entirely with the mouth. In 1818, the first rotary valves were patented for the horn; piston valves appeared in 1839. Valves allow players to sound all the notes in the chromatic scale, and certain notes that had always been difficult to play in tune became both easier, more accurate, and more pleasing to the ear.

Robert Schumann began discovering the horn’s potential as a solo instrument in 1843, when he composed a chamber work that included two natural (valveless) horns. Six years later, Schuman wrote a duet for (valved) horn and piano; the improved sound of the valve horn pleased Schumann so much he immediately set to work on a piece for four horns and orchestra. Schumann’s title, Konzertstücke, is misleading, as it suggests a short and rather inconsequential work. Op. 86 is anything but, and the heroic quality of four solo horns makes for bravura listening. In the opening Lebhaft (lively), the four horns sound a series of muscular fanfares and legato phrases that showcase the horn’s warmth.

Schumann’s writing covers the full spectrum of the horn’s melodic range, in a manner designed to showcase the improved sound of the valved horn. The central Romanze features a series of warm, sometimes plaintive tunes, which the horns play in close harmony, producing a rich buttery sound. A series of horn calls signal the transition to the closing Finale (Sehr lebhaft – very lively), which returns us to the exuberant, irrepressible joy of the first movement.

Symphony No. 8 in G Major,

Op. 88, B163

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK (1841 –1904)

Composer: born September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, near Kralupy (now the Czech Republic); died May 1, 1904, Prague

Work composed: Dvořák wrote the Symphony No. 8 between August 26 and November 8, 1889, at his country home, Vysoká, in Bohemia. The score was dedicated “To the Bohemian Academy of Emperor Franz Joseph for the Encouragement of Arts and Literature, in thanks for my election [to the Prague Academy].”

World premiere: Dvořák conducted the first performance in Prague on February 2, 1890

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings

From its inception, Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony in G major was more than a composition; in musical terms it represented everything that made Dvořák a proud Bohemian. Trouble began when Dvořák’s German publisher, Fritz Simrock, wanted to publish the symphony’s movement titles and Dvořák’s name in German translation. This might seem like an unimportant detail over which to haggle, but for Dvořák it was a matter of cultural life and death. Since the age of 26, Dvořák had been a reluctant citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, ruled by the Hapsburg dynasty. Under the Hapsburgs, Czech language and culture were vigorously repressed.

Dvořák, an ardent Czech patriot who resented the Germanic norms mandated by the Empire, categorically refused Simrock’s request. For his part, Simrock was not enthusiastic about publishingDvořák’s symphonies, which didn’t sell as well as Dvořák’s Slavonic dances and piano music. Simrock and Dvořák also haggled over the composer’s fee; Simrock had paid 3,000 marks for Dvořák’s Symphony No. 7, but inexplicably and insultingly offered only 1,000 for No. 8. Outraged, Dvořák offered his Symphony No. 8 to the London firm Novello, which published it in 1890.

The G Major symphony broke new ground; it was, as the composer explained, meant to be “different from the other symphonies, with individual thoughts worked out in a new way.” This “new way” refers to Dvořák’s musical transformation of the Czech countryside he loved into a unique sonic landscape.

Within the music, Dvořák included sounds from nature, particularly hunting horn calls and birdsongs played by various wind instruments. Biographer Hanz-Hubert Schönzeler observed, “When one walks in those forests surrounding Dvořák’s country home on a sunny summer’s day, with the birds singing and the leaves of trees rustling in a gentle breeze, one can virtually hear the music.” Serenity floats over the Adagio. As in the first movement, Dvořák plays with tonality; E-flat major slides into its darker counterpart, C minor.

Dvořák was most at home in rural settings, and the music of this Adagio evokes the tranquil landscape of the garden at Vysoká, Dvořák’s country home. In a manner similar to Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, the music suggests an idyllic summer’s day interrupted by a cloudburst, after which the sun reappears, striking sparkles from scattered raindrops. During a rehearsal of the trumpet fanfare in the last movement, conductor Rafael Kubelik declared, “Gentlemen, in Bohemia the trumpets never call to battle – they always call to the dance!” After this opening summons, cellos sound the main theme. Quieter variations on the cello melody feature solo flute and strings, and the symphony ends with an exuberant brassy blast.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

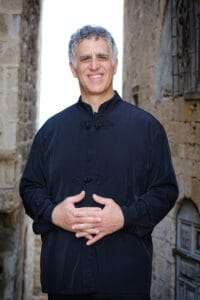

Nir Kabaretti

Internationally acclaimed conductor, Nir Kabaretti, is the Music and Artistic Director of the Santa Barbara Symphony in California, and the Israel Sinfonietta Beer Sheva.

Described as “a conductor with immense musicality and warm personality” by his mentor Maestro Zubin Mehta, Kabaretti has earned an impressive reputation across continents for his command of a vast symphonic, operatic and ballet repertoire.

Maestro Kabaretti has worked with some of the world’s most sought-after musicians, leading opera houses, and renowned orchestras. Some of his collaborators include Lang Lang, Placido Domingo, Joyce Di Donato, Itzhak Perlman, Vadim Repin and Hélène Grimaud.

As guest conductor, Kabaretti keeps a busy international schedule throughout the year. Some of his appearances have included the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Orchestra del Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, Orchestra Filarmonica Arturo Toscanini, Orchestre Philharmonie Royale de Liège, Philadelphia Chamber Orchestra, Chicago Philharmonic, National Taiwan Symphony Orchestra, Orquesta Filarmonica de Buenos Aires, Orquesta Filarmonica de Bogotà, Orchestre National du Theatre du Capitole de Toulouse, Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne, Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano “La Verdi”, Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, Zagreb Philharmonic Orchestra, Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra, Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, Vienna Chamber Orchestra, Orquesta Sinfonica de Madrid, Orquesta Filarmonica de Gran Canaria, Real Orchesta Sinfònica de Sevilla and the Bochumer Symphoniker.

Kabaretti’s Opera and Ballet productions include The Diary of Anne Frank, a guest production of the Vienna State Opera performed at the Bregenz Festival and Expo 2000 in Hannover. In 2004 Kabaretti made his debut at Teatro alla Scala di Milano and 2005 lead Teatro San Carlo di Napoli on its first tour to Japan, conducting Il Trovatore both in Kyoto and Tokyo. In 2010, Kabaretti debuted at the summer season of the Caracalla Roman Bath in Rome, and in 2019 made his debut at the Puccini Festival with Madama Butterfly. 2023 started for Maestro Kabaretti with a debut in Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles.

Nir Kabaretti recorded for Deutsche Gramophone 5 CD’s of modern piano concerti for young pianists, a DVD of Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream with Teatro alla Scala in Milan, and in 2022 he recorded with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Pianist Roberto Prosseda four Italian Piano Concerti of the 20th century.

Graduated from the University of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, Kabaretti was appointed Chorus Master of the Vienna State Opera and the Salzburg Festival. Other positions in his early career include assistant to the Music Director of Teatro Real in Madrid and Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, in Italy, and Music Director of the Raanana Symphonette Orchestra in Israel. He served as the Music Director of the Southwest Florida Symphony between 2014-2021.

Nir Kabaretti received the America-Israel Cultural Foundation Grant for Young Conductors. In 1993, he won the Forum Junger Künstler Conducting Competition in Vienna. In 1994 he was among the finalists in the International Competition for Conductors in Douai, France.

Nir Kabaretti is fluent in English, German, Italian, Spanish and Hebrew.

Read LessConcert Sponsors

Tiemens Private Wealth Management Group of Wells Fargo Advisors

Marty Kelley

Lt. Col. (Ret) Eugene S. Harsh

Concert Co-Sponsors

Michael and Patricia Olsen

Marjorie Rapp

Walter K. and Janet G. Gerber

Lance and Brenda Miller

Barbara A. and Dr. Robert E Carlton Fund of the Foundation

MacKenzie Place

Phil and Carolyn Erdle

Guest Artist Sponsors