Elgar’s Enigma

190 S. Cascade Ave

Colorado Springs,

CO

80903

United States

+ Google Map

Program

Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. 2

Elgar Enigma Variations

About The Performance

Edward Elgar came from humble beginnings at a time when the world was changing. He rose to become one of England’s most revered composers. His mysterious “Enigma” hides its secret inside a treasure box of musical variations including the world-famous “Nimrod.” Special guest pianist Jorge Luis Prats joins forces with the maestro and musicians of the Philharmonic for Sergei Prokofiev’s second piano concerto.

Join us for Pre-Concert talks, beginning one hour before performance time.

Read More

Piano Concerto No. 2 in G Minor,

Op. 16

SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891 – 1953)

Work composed: original version 1913; reconstructed/rewritten in 1923. Dedicated to the memory of Maximilian Schmidthof, a classmate and close friend of Prokofiev’s at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Schmidthof committed suicide in the spring of 1913, just as Prokofiev completed Op. 16.

World premiere: First version: at the Vauxhall in Pavlosk, outside Moscow, on September 5, 1913, with Prokofiev at the piano. Second/revised version: Serge Koussevitzky conducted, with Prokofiev again at the piano, in Paris on May 8, 1924.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, tambourine, and strings.

About the Piece

The 1913 premiere of the original version generated intensely negative audience reaction, of which the following account is typical: “Seats emptied one by one. At last the Concerto came to an end … most of the audience were hissing and shouting angrily. ‘To hell with this futurist music!’ people were heard to exclaim. ‘The cats on the roof make better music!’ Most Russian critics savaged the young composer, but the more open-minded Vyacheslav Karatygin presciently remarked that the audience’s hisses were of no consequence. “Ten years from now it [the public] will atone for last night’s jeering by unanimously applauding a new composer with a European reputation.”

In his diary, Prokofiev described the audience’s reaction: “I came out twice to acknowledge the reception, hearing cries of approval and boos coming from the hall. I was pleased that the concerto provoked such strong feelings in the audience.” The solo piano begins the Andantino with a romantic, mysterious melody; the winds dialogue with the piano as the theme repeats. A bouncier, agitated counter-melody is unveiled by the piano; however, it is the primary theme that dominates the majority of the first movement, which is developed and rearticulated in an extended solo section for the piano.

The Scherzo’s 2.5 minutes of dazzling scale passages and eye- and ear-popping virtuosic tricks for the soloist is juxtaposed with the Intermezzo’s elephantine ostinato in the low strings, punctuated by dissonant blats from the brasses. The piano music’s weight and power has a raw, primitive edge; this section may have sparked the 1913 audience’s reaction. In the closing Allegro tempestoso, Prokofiev unleashes fire and energy, and gives the pianist an extended solo. The concerto ends with a return to the fourth movement’s opening brilliance and irrepressible energy

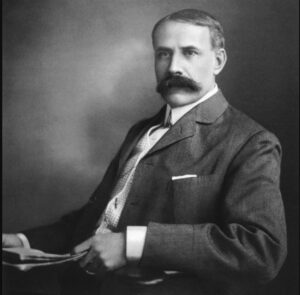

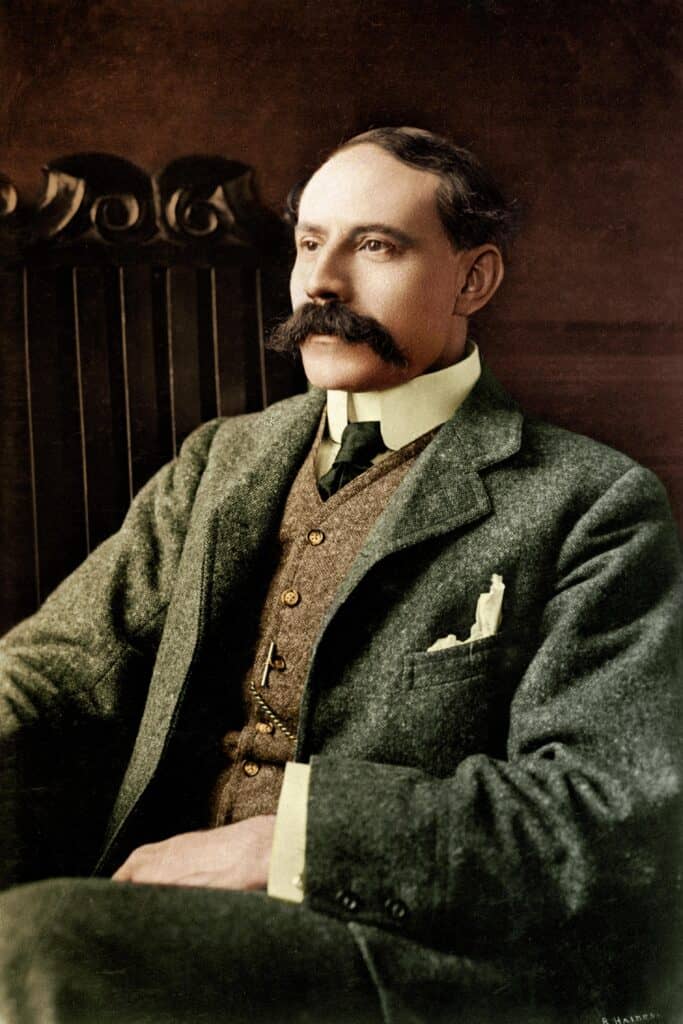

Enigma Variations

EDWARD ELGAR (1857 – 1934)

Composer: born June 2, 1857, Broadheath, near Worcester, England; died February 23, 1934, Worcester

Work composed: Oct. 21, 1898-Spring of 1899 and dedicated “to my friends pictured within.”

World premiere: June 19, 1899, under the direction of Hans Richter at St. James’ Hall, London. At Richter’s suggestion (along with that of Elgar’s publisher, August Johann Jaeger), Elgar later wrote an extended finale, which he himself conducted at the Worcester Festival on Sept. 13.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, triangle, organ, and strings

About the Piece

Edward Elgar’s Variations for Orchestra on an Original Theme, Op. 36, better known simply as the Enigma Variations, poses an intriguing mystery, which has never been solved. There are two enigmas in the Variations: one opens the piece; the other is silent but present throughout. Much has been written about the Variations, including lengthy discussions of their actual title. Elgar called them simply Variations for Orchestra on an Original Theme, and later added the word “Enigma” in the manuscript, although he never referred to them as the “Enigma Variations” in his conversations and correspondence.

Regarding the theme of the enigma itself, Elgar wrote in the notes for the first performance: “The enigma I will not explain — its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the apparent connection between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’ but is not played.” The second enigma, the silent theme, has sparked much speculation, from “Rule Britannia” and “God Save the King” to “Auld Lang Syne” or “Ein feste Burg” (A Mighty Fortress).

Some suggest the second enigma is not a musical theme at all, but rather an abstract concept, such as friendship or love. In 2010, two musicologists published a paper suggesting the enigma was pi (π), the ratio of a circle’s diameter to its circumference. The Variations marked a new phase in Elgar’s career. His previous works, primarily for chorus and orchestra, had brought him fame within England, but he remained largely unknown elsewhere. When the renowned Austro-Hungarian conductor Hans Richter agreed to premiere the Variations, he also became their champion, introducing them (and Elgar) to audiences throughout England and Europe.

The audible “Enigma” theme represents Elgar himself (he felt it embodied the loneliness of the creative artist) and heused it again in The Music Makers of 1912. It came to him one evening in October of 1898 while he was improvising at the piano. He recalled, “Suddenly my wife interrupted by saying, ‘Edward, that’s a good tune.’ I awoke from the dream, ‘Eh! Tune, what tune?’ and she said, ‘Play it again, I like that tune.’ As he repeated it, he began to vary it, asking her, “Whom does that remind you of?” and thus the caricatures of the “friends pictured within” were born. Elgar indicated each person represented:

1. C.A.E. Caroline Alice Elgar, Elgar’s wife.

2. H.D.S-P. Hew David Steuart-Powell, an amateur pianist with whom Elgar played in chamber ensembles.

3. R.B.T. Richard Baxter Townshend, an eccentric scholar/author whose caricature of an old man is the subject ofthe variation.

4. W.M.B. William Meath Baker, the squire of Hasfiel Court, whose habit of slamming doors upon exiting rooms is heard in this variation 5. R.P.A. Richard Penrose Arnold, son of poet Matthew

Arnold, known as a daydreamer.

6. Ysobel Isabel Fitton, an amateur violist.

7. Troyte Arthur Troyte Griffith, an artist and architect and a pianist of limited skill, hence the bombastic quality of his variation.

8. W.N. Winifred Norbury, secretary of the Worcestershire Philharmonic Society (this variation is actually a portrait of her stately house, the scene of numerous musical gatherings; it also captures her ready laugh).

9. Nimrod August Johannes Jaeger, a good friend and one of Elgar’s publishers at Novello (Nimrod is the biblical “mighty hunter,” a pun on “Jaeger,” German for “hunter.”) Elgar described the variation as an evocation of a conversation between the two men about Beethoven’s difficulties with his deafness. Jaeger’s mention of Beethoven was meant to encourage Elgar, despondent over his own struggles to gain recognition, to continue composing. Elgar wrote, “it will be noticed that the opening bars are made to suggest the slow movement of [Beethoven’s] Eighth Sonata (Pathétique).”

10. Dorabella Dora Penney (later the wife of Richard Powell) nicknamed “Dorabella” by Elgar, who borrowed the name from Mozart’s opera, Così fan tutte. She was a close friend of the Elgars’ and often sat at the piano turning pages for Elgar during performances.

11. G.R.S. George Robertson Sinclair, organist of Herefor and owner of a bulldog named Dan. The variation actually portrays Dan fetching and retrieving sticks from the Wye River.

12. B.G.N. Basil Nevinson, an amateur cellist who played with Elgar and Steuart-Powell.

13. *** Possibly Lady Mary Lygon, who traveled to Australia around the time Elgar composed her variation. In it he quotes from Mendelssohn’s Calm Seas and Prosperous Voyage. This variation may also refer to Elgar’s former fiancée, Helen Jessie Weaver, who, by all accounts, broke his heart when she ended their engagement and emigrated to New Zealand.

14. E.D.U. Elgar. “Edoo” was Alice’s pet name for her husband, a variation of the French “Edouard.” His variation quotes from hers and from Jaeger’s, the two people who always believed in and supported him.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

Read LessConcert Sponsors

Arlen Feldman and Adriana Wood

Katherine H. Loo

The Bloom Foundation

Concert Co-Sponsors

Stephen and Maxine Glassey

Lance and Brenda Miller

Guest Artist Sponsors